|

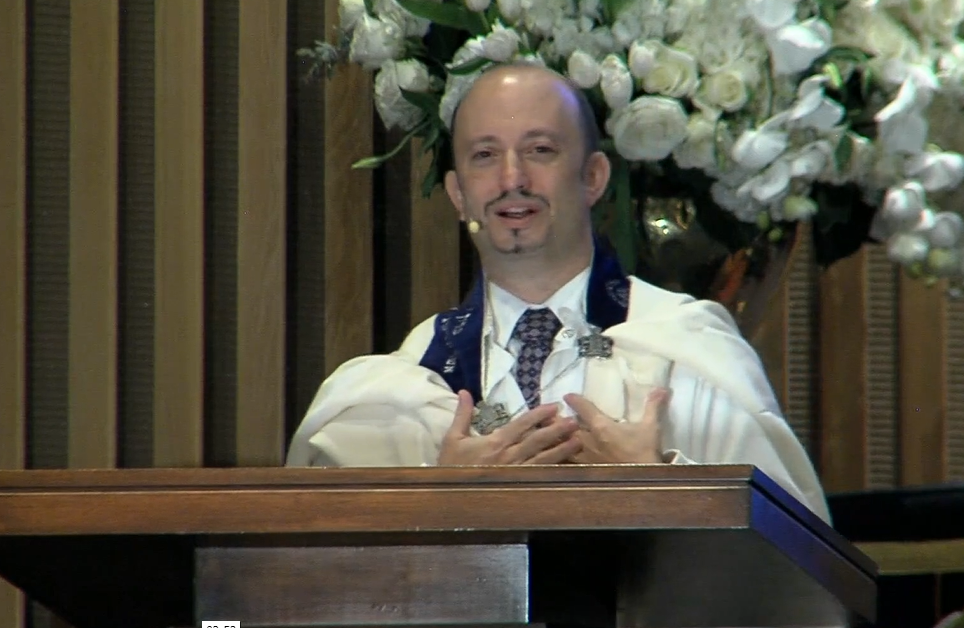

Yom Kippur Sermon 5781

Rabbi Ari Sunshine Congregation Shearith Israel Today I thought I’d open my remarks with a few words about food. Dangerous territory in which to tread on a fast day, right? 😊 On the bright side, at least I’m confident I’ll have your, or your stomach’s, attention now. That is, until I tell you what food I wanted to talk about. You see, I wanted to talk about matzah. You heard me right, matzah. I know what you’re thinking. Rabbi, of course it makes total sense for you to talk about a food, matzah, in the midst of a fast day half a year away from Pesach. But now you must admit, you’re a little curious where I might be going with this. So let’s find out. 😉 It seems strange that the Torah and our tradition would choose such a shvach, non-descript food as the symbol of one of the most iconic and formative moments in our people’s history, our miraculous deliverance from slavery through God’s metaphorical hands. Why not a symbol that represented power or perhaps at least greater flair? Somehow it’s a simple unleavened bread, referred to as lechem oni, typically translated as “bread of affliction”, that is the calling card for our people as we became a free nation. How does that have anything to do with the process of redemption? The Maharal of Prague, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Betzalel, a 16th and 17th century sage also known for his legendary associations with the Golem, offers an answer in his work Gevurot Hashem. He explains that matzah is called lechem oni because it is the opposite of enriched, or egg, matzah with its added oils or honey, since the oni, meaning “poor person” in Hebrew, has no money; he has only himself. Instead of framing matzah as the “bread of affliction”, the Maharal looks at it as essentially “simple bread”, with no additives or sweeteners, just flour and water, which is a perfect symbol for the “oni”, the poor person who has nothing except for the absolute basics. The Maharal’s take is that the poor person, while not being in a great position financially, is essentially unshackled from the physical world, unburdened from it, and thus MORE free than someone who has a great many possessions and a standard of living to maintain. It’s a representation of autonomy that, while coming with its own challenges, is quite different than the slave, in Egypt or anywhere, who is beholden to his or her master’s bidding. So the Maharal teaches that we are commanded to eat this simple, poor bread on the original night of the Exodus and every Pesach since. Neither the matzah, nor we as the people Israel and as individual Jews, are weighed down on the night of our redemption by any extra ingredients—save for maybe the debatably worth it pareve flourless cake, sorry, couldn’t resist 😊—it’s just us, and God, together, existing outside of the bonds and burdens of slavery. A simple but fulfilling life. Well, a quick flip through the rest of the Torah after the Exodus, in particular the book of Numbers, suggests that the relationship between Israel and God was, well, COMPLICATED. Challenges, baggage and distractions seeped into the mix, and the relationship got a lot harder. LIFE got a lot harder, which seems only natural when you’re wandering in a wilderness for a long period of time. And this led to questionable choices and prioritizations on the part of the Israelites. And yet God pines, if you will, for a return to that simple, original and pure state of the relationship, as the words of Jeremiah 31:20, which we heard last week during the Zichronot section of Musaf, attest: “Ha-ven yakir li, Ephraim, truly Ephraim is a dear son to Me, im yeled sha’ashu’im, a child that is dandled, ki midei dabri bo, zachor ezk’reinu od, whenever I have turned against him, My thoughts would dwell on him still; al ken hamu me’ai lo, that is why My heart yearns for him, rachem arachameinu, n’um Adonai, I will receive him back in love, declares Adonai”. We may have strayed from who we were as simple, free Israelites just out of Egypt, but there’s always a pathway back to that special snapshot in time and that treasured relationship with God. And, time and time again, the Israelites end up getting a wake-up call to this reality, either by hearing it from one of the prophets, or by dealing with an external crises that highlights the importance of a reboot and a return to the simplicity of their core relationship with God. In a number of ways the experience we’ve been going through as individuals, as families, as a community, and as a society over these last six months is quite similar to what our biblical ancestors went through. An external crisis, a pandemic, has gotten our attention, dramatically altered our way of life, and shaken us to our core. As businesses of all kinds and all around us—restaurants, retail shops, movie theaters and others—have been forced to close or re-organize and re-prioritize to find ways to be profitable in the COVID era and its aftermath, and we have been largely isolating ourselves in our homes, the theme of change management looms large in our lives. The world has gotten even more complicated around us—how have we adapted and responded to that change? One of the most common answers I’ve been seeing and hearing to this question in our community and in society in general is that we’ve been forced to simplify things. To go back to the basics. A number of you have specifically shared with me in these recent months how profound this change has been for you, and how grateful you are that you have been forced to re-examine your life choices and priorities and embrace a simpler life. Cooking together and enjoying daily meals as couples or families at the kitchen table, or socially distanced in the backyard with other extended family members and friends. Walking, hiking, running, or biking to be out in nature and get exercise and take care of our bodies. Playing games. Reading books and taking online classes. More frequent calls or FaceTimes or Zooms with your friends and loved ones, even folks you hadn’t been in touch with in a long time. Seeking community and connection with the shul and with God. In a real sense, what we are taught in the opening words of the biblical scroll of Ecclesiastes seems to ring true now more than ever: “Havel havalim, ha-kol havel”, vanity of vanities, everything is utterly futile—framed dramatically for rhetorical flourish, yes, but meaning that most everything we have in life is extra “stuff”, and is never meant to last. What is not havel, futile or vain, are these basic core building blocks of our lives. Those are meant to last and remain constant if we only choose to prioritize and nurture them. 19th century American author Henry David Thoreau looks to have been cut from the same philosophical cloth as Ecclesiastes. Unlike Ecclesiastes, though, whose reflections seem to have emerged from living in the metaphorical “fast lane” of the societal highway, Thoreau’s desire to understand and examine the worth and meaning of life, and to strip it down to its most basic elements, led him to live in isolation for two years in a small house on the shores of Walden Pond. Reflecting in his work Walden on the reasons for having made this decision, Thoreau wrote, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion”. And Thoreau added: “Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind”. Whether we frame it through the experiences and reflections of Ecclesiastes or Thoreau, or through the lens of our own recent life experiences, perhaps at this moment in our lives we can realize that we may have been spending too much time and energy on non-essential things. Thoreau advises us in Walden, “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand”. The essence of his, and Ecclesiastes’, message, is clear: cut out what’s unnecessary and focus on what’s important. And this return to basic values and priorities, my friends, is actually the essence of teshuva, the process of “returning” to ourselves, to our community, and God with which we are tasked during these Yamim Noraim, these High Holy Days. When a properly run organization is going through a process of change management and strategic planning, as we did here at Shearith two years ago, it starts with identifying its mission, vision and values to make sure it is focusing on its core essence, BEFORE moving forward and figuring out what kind of change is necessary. So, too, with each of us as individuals. We can’t begin the process of successful change until we strip ourselves down to our core essence and then see what’s been getting in the way of us being our best selves. We can then cut those obstacles or distractions out and focus on what’s most important. At the end of the biblical scroll of Lamentations, we read a phrase that is likely more familiar to many of us from the conclusion of the Torah service when we return the Torah to the ark. “Hashiveinu Hashem eylekha v’nashuva, chadesh yameinu k’kedem”, “Bring us back to you, O God, and we shall return, renew our days as they were before”. When we think of renewal, we might first make the mistake of getting bogged down in the root “new” and understand it as something emerging from scratch. But here are some definitions of renewal: an instance of resuming an activity or state after an interruption; repairing something that is worn out, run-down, or broken; the act of being made fresh or vigorous again. And so our scripture reminds us that renewal and change actually starts with a return to where, and WHO, we were, back when we were at our best, and picking back up from where we left off then. When our hearts were focused on the right things. When we channeled more of our time into pursuing and committing to those relationships that mattered. As with our Israelite ancestors, life got complicated, and some of these basic priorities got away from us and became worn down or broken. But these last six months we’ve been challenged to figure out how we’re going to make it through the wilderness of COVID and emerge stronger from it. We have been forced to simplify, to get back to being like the matzah, the no-frills symbol of our people when we first got our start in relationship with God once Egypt’s oppression was stripped away. How do our best selves and lives look? When we are deeply connected in relationships, in person or virtually, with family, friends, and community who are the strongest anchors in our lives; when we are focused on maintaining our health by taking precautions and exercising; when we are reading and learning and expanding our appreciation for, and understanding of, our world in general and also of our Jewish tradition specifically, and thinking about how we can contribute to the world and to the continuing chain of Jewish generations; and when we are cultivating our faith in, and commitment to, God who can also be a rock for us even in the most turbulent of times. This is what our best selves look like, and what teshuva looks like, this year and every year. And so we pray together with the familiar words: Hashiveinu Hashem eylekha v’nashuva, chadesh yameinu k’kedem. Bring us back to you, God, and we shall return, to being our best selves and focusing on what matters. Renew our days and clear away the distractions from our souls so that we may once again be fresh and vigorous in the pursuit of meaning in our relationships and in our lives and in our commitment to you and to serving as your agents of goodness in your world. And let us all say, AMEN.

3 Comments

Joint Sermon for Erev Rosh Hashanah 5781/2020

Rabbi Ari Sunshine, Rabbi Adam Roffman and Rabbi Shira Wallach Congregation Shearith Israel From the day Adam and Eve were exiled from the garden of Eden, they lived together East of Eden, tilling the earth, raising children and struggling to stay alive. After those many years of struggle, when their children were grown, Adam and Eve decided to take a journey before it was too late and see the world that God had created. They journeyed from one corner of the world to the other and explored all of the world's wonders. They stood up on the great mountains, treked across the vast deserts, walked amid the mighty forests, and traversed the magnificent seas. They watched the sunrise over the endless wilderness and saw it set into the boundless ocean. All that God had created they beheld. In the course of their journeys, wandering from place to place, they came upon a place that seemed so familiar. They came upon the garden of Eden from which they had been exiled on the very first day of their lives. The garden was now guarded by an Angel with a flaming sword. This Angel frightened Adam and Eve who fled. Suddenly they heard a gentle imploring voice. God spoke to them: “My children, you have lived in exile these many, many years. Your punishment is complete. Come now and return to my garden. Come home to the garden.” Suddenly to the Angel disappeared. The way into the garden opened and God invited them in. But Adam, having spent so many years in the world, had grown shrewd. He hesitated and said to God, “You know it has been so many years. Remind me, what is it like in the garden?” “The garden is paradise,” God responded. In the garden there is no work. You need never struggle or toil again. In the garden there is no pain, no suffering. In the garden there is no death. In the garden there is no time: no yesterday, no tomorrow, only an endless today. Come my children, return to the garden.” Adam considered God's words. He thought about a life with no work, no struggle, no pain, no passage of time, and no death. An endless life of ease with no tomorrow and no yesterday. And then he turned and looked at Eve his wife. He looked into the face of the woman with whom he had struggled to make a life, to take bread from the earth, to raise children, to build a home. He read in the lines of her face all the tragedies they had overcome and the joys they had cherished. He saw in her eyes all the laughter and all the tears they had shared. Eve looked back into Adam's face. She saw in his face all the moments that had formed their lives: moments of jubilant celebration and moments of unbearable pain. She remembered the moments of life-changing crisis and the many moments of simple tenderness and love. She remembered the moments when a new life arrived in their world and the moments when death intruded. As all their shared moments came back to her, she took Adam's hand in hers. Looking into his wife's eyes, Adam shook his head and responded to God's invitation. “No thank you,” he said. “That's not for us not now. We don't need that now. Come on Eve,” he said to his wife. “Let's go home.” And Adam and Eve turned their backs on God's paradise and walked home. It’s interesting, that on this evening, when we celebrate the creation of the universe, we don’t usually recount its story. Not tonight, not tomorrow, not the next day. Ironically, Rabbi Ed Feinstein’s beautiful retelling of the exile from Eden might help us understand why. In his version of the story, God reopens the gates, allowing Adam and Eve an opportunity to return to the perfection He created for them before they corrupted it. And yet, they refuse, deciding instead to make their own way in the world. Why? Because what they realize after a long period of struggle and hardship is that there is more meaning, more possibility, and more humanity in a world that is imperfect. In Eden, there is no conflict, so there is no growth. In the garden of the Divine, there is nothing to work for, because everything is provided for you. In the realm of the Godly, there are no problems to solve, and nothing to build. It may seem like the world we live in right now couldn’t be farther removed from Gan Eden or a conventional definition of paradise, and yet what drives us isn’t a return to idyllic isolation from a complicated and demanding world, but rather a way to ground ourselves so we can engage fully with that world. Like Adam and Eve after the fall, we live in a world where we are called, day after day and year after year for 5780 years and counting, to help reinvent and recreate in partnership with God. Every morning, before we say the Shema, we praise God for being m’chadesh b’tuvo b’khol yom tamid, ma’aseh bereishit—the one who is constantly renewing and re-creating our world, and charges us to do the same as much as we are able. We are the ones who, inspired by the teachings of our Torah, decide what sacred space is, where we learn, how prayer is offered up to heaven, and how we lift each other up right here on this earth. This year, we have truly recreated all of these experiences anew. We have been challenged to find connection with each other and with God, despite the awful circumstances in the world around us. And how have we fared in these endeavors? We have re-defined the possibilities of sacred space. We already knew we could find it in our synagogue building while doing things such as davening or learning or packing sandwiches for the sandwich drive, and experience it while outside the walls of the shul studying Torah together in a bar or restaurant, delivering Shabbat meals to some of our homebound seniors, or enjoying a weekend away at the Family Retreat or a week and a half on a congregational mission to Israel. But did we know before this year that we could also create and enter sacred space when we assemble in our little boxes on a Zoom screen, and form daily or Shabbat minyanim, share a meal in a virtual breakout room for Shabbat Across Shearith, or assemble for Havdalah online every weekend with a number of congregants joining in from their homes with their own Havdalah sets? We have expanded our notion of where we can learn, and developed our tech skills even when many of us felt we had none, connecting with teachers and fellow eager learners in accessible and versatile mobile classrooms for adults and children of all ages, and learning a lot of patience (and how to mute and unmute!) along the way, looking forward to the day when we can again discuss and debate with our fellow students across the table from one another. We have broadened our perspectives on how we can offer our prayers to God. In the absence of our ability to gather in one room for a minyan, we have greeted each other warmly onscreen, turned to digital versions of our liturgy when we didn’t have siddurim handy, met the powerful emotional and ritual need of reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish for our loved ones, and even figured out how to sing together as a group without ACTUALLY singing together with our fellow worshipers. And we have innovated ways to lift each other up amidst the peaks and valleys of our lives, extending virtual embraces whether celebrating a Bar Mitzvah or a bris or a baby naming, or offering heartfelt condolences to mourners at a funeral or a shiva while others quietly listen in rapt attention to the warm memories being shared. One common thread links all of these experiences together, and that is community. Whether we are in each other’s physical presence, or seeing each other’s faces online, or even some of both, we can create a powerful sense of sacred space, we can learn and grow together, we can worship and break bread together, and rejoice or mourn together. In this we draw strength from the precept imparted to us at creation--lo tov heyot he’adam levado, we do not go through life alone, but with companionship in community. And it’s this last point that we’d like to emphasize on this erev Rosh Hashanah, as we begin this season of High Holy Days together--not in our beautiful sanctuaries, in the seats that some of our families have occupied for generations-but in a way none of us could have possibly imagined a year ago-spread out across the city in our own homes, very far from Gan Eden. In Rabbi Feinstein’s story, Adam and Eve decline the opportunity to return to Eden. It may be paradise, but it’s not home. Because, you see, as humans we also get to define what home means to us. Home isn’t defined by perfection. Instead we may define it in its broadest sense as a place where we feel loved and valued, comfortable and comforted, where we experience joy and laughter, where we break bread, where we struggle and where we grow. No matter how crazy the world is around us, those constants remain. For Adam and Eve, companionship was the key to these constants being realized. And with that in mind, I’d like to ask each of you to reach into your High Holy Days Box and take out and unwrap the special gift we’ve included for you. I’ll give you all a moment so you can untie the ribbon and take out what’s inside the box. As you can see, we’ve given you a compass. A compass will always point out your “true north” and let you know where to find it, even if you’re lost in a forest filled with trees and can’t see which way to turn to get home, or just feeling lost in a world that feels decidedly un-Eden like. Friends, throughout these High Holy Days, before each private Amidah prayer that we recite, we hope you’ll try picking up this compass to orient yourselves eastwards toward Yerushalayim in your prayers, as well as link yourselves symbolically, along with your fellow congregants wherever they may be located, to the unfailing true north of companionship and community which you can count on here at Shearith Israel, where we are so much more than a building. We are a strong, vibrant and caring community where we hope you will always feel that sense of home I just described a few moments ago. Whether we’re online as we are right now, in person as we hope to be very soon, or some combination of both, we remain, Shearith Israel, here for you in good times and bad, a community where you can Enrich Your Life, Elevate Your Soul, and Embrace Your Judaism. We look forward to establishing new relationships and connections, and strengthening longstanding ones, as together we journey forward into this next chapter of creation, the as yet unwritten story of 5781, one which we hope will be filled with sweetness, growth and good health for all. Shana Tova, and Shabbat Shalom  Rosh Hashanah Sermon 5781 9/19/2020 Rabbi Ari Sunshine Congregation Shearith Israel Some folks are called gym rats for their intense devotion to working out, or practicing their chosen sport or sports. My Dad, however, is what I’d affectionately refer to as a “shul rat”, someone who just LOVES to be in shul. It could be at his shul, Har Shalom in Potomac, Maryland, where my classmate and dear friend and a former member of Shearith’s rabbinic team, Adam Raskin, is now his rabbi. It could be when he goes and leads services for the residents of Revitz House, a Jewish senior living facility in Rockville, Maryland. It could be when he’s traveling in the U.S. or elsewhere around the world. Wherever he is, he wants to be in shul on Shabbat. In this regard, the circumstances of the COVID pandemic have actually provided him with a small but meaningful silver lining while he and my Mom largely continue to shelter at home. Because, you see, any given Shabbat morning, my Dad can hop on two, three, or as many as five online Shabbat services, joining the Shabbat community in shuls all around the U.S—and the difference in time zones sure helps with that! Ok, admittedly he has a few favorites, whether it be Har Shalom, or Shearith where he gets to watch his son do the rabbi thing, or Beth Am in Baltimore where my cousin is the rabbi, and a handful of others. But I get a kick out of talking with him and my Mom after Havdalah or on a Sunday and hearing him say, “I went to three shuls today!” or telling me that he went to shul with his sister, my Aunt Bette, that morning. Of course, Bette was sitting in her home in Ann Arbor, MI, and my Dad was in his home in Maryland. And yet they shared the same shul experience and it was as if they were sitting next to each other, able to kibitz about the rabbi’s sermon (chances are the reviews are usually fairly positive when they’re watching one of their children preach), and the tune that was used for Adon Olam. The world has gotten considerably smaller during these past six months. Certainly my family’s ability to “go to shul” together online on Shabbat is not the only example of this. How many of you watching today shared one or more Pesach seders this year with friends and loved ones all over the country? Yes, it’s true we could say “dayenu” at this point to the problem of not being able to sing together on the same beat, but weren’t the “Zeders” of 2020/5780 pretty special in their own way, effectively expanding our Seder tables to include folks who wouldn’t all otherwise have necessarily been able to join us? And we can say the same thing about brises, simchat bat ceremonies, b’nei mitzvah, funerals, and shiva minyanim, where family members and friends from faraway places have been able to smile and celebrate onscreen with us, or comfort us with their presence, which even as recently as the beginning of 2020 would not have been considered as an option for people, let alone one that so many folks are now taking advantage of to draw closer to those they care about. Finally, let’s not forget that this closeness has not been limited to the boundaries of the U.S. Back in June we arranged a virtual tour for our congregation of Gabrieli Weaving’s studio in Rechovot, Israel and store in Jerusalem. We got a glimpse behind the curtain of what I would argue is the best source in the world for beautiful tallitot, from which more than 2/3 of my 16 tallitot—not a misprint—come, and a number of our members purchased tallitot for themselves, their children or their grandchildren, including several of our Shearith B’nei Mitzvah families, after setting up personal shopping appointments. We were 7000 miles and 8 hours on the clock apart, and yet there we were, connecting intimately and forging or strengthening our bond to Israel and to Jewish ritual at the same time. And we wouldn’t even have thought of trying this a year ago. Yes, the world definitely feels smaller than it used to feel. Our reach and capacity to connect with others has been extended exponentially, which has opened up new opportunities for us personally and professionally. But what are the implications of this for us going forward, as we continue to grind our way through a pandemic, but also prepare for its eventual aftermath? Does our ability to reach further challenge us to think about widening our circle of concern, or is this just a short-term way of thinking that should yield to insularity and parochialism once things “go back to normal” within our communities or in general with the practice of our Judaism? Friends, I would suggest that the answer to this question is found in Jewish values, and it gets back to the very core of how we see ourselves as Jewish people relative to the rest of the world. Deeply ingrained in our traditional texts and our prayer liturgies are many reflections of this basic tension, the tension between particularism and universalism. Take the Aleinu prayer for instance. It’s a prayer many of us know well and can sing along with, but how well do we really know it? You might know a little more about it if you watched my On Demand video clip on it on the portal, but otherwise feel free to check that and our other On Demand content out later. The prayer begins, “Aleinu l’shabeach la-Adon ha-kol, lateyt g’dulah l’yotzer b’reishit, she-lo asanu k’goyei ha’aratzot, v’lo samanu k’mishp’chot ha-adama, she-lo sam chelkeynu ka-hem, v’goraleinu k’chol ha-monam”—It is for us to praise the Ruler of all, to acclaim the Creator, who has not made us merely a nation, nor formed us as all earthly families, nor given us an ordinary destiny. In these opening lines of the Aleinu, as Jewish people we are called upon to praise God as the master and creator of all, BECAUSE God assigned us a different kind of responsibility and destiny in the world. Over the course of the full text of the two paragraphs of the Aleinu, we reflect back on God as the universal creator, and yearn for the day when we will be able “l’taken olam b’malchut Shaddai”, to establish the world in the kingdom of the Almighty, or, in modern usage, to repair the world according to God’s blueprint, a world that includes, as our machzor says in a comment on p.156, “the relief of human suffering, the achievement of peace and mutual respect among peoples, and protection of the planet itself from destruction”. And then, at the conclusion of the prayer, when we cite the words of the prophet Zechariah, we hope that the day will also come when our God will be acknowledged as the one God who is sovereign of all the earth. Once again, we are pulled back and forth between universal and particular aspirations. Aleinu is actually one of a number of prayers in our High Holy Day liturgy that reflects themes that are both particularistic towards the Jewish people and universalistic towards all of humanity. This should not surprise us when we recognize that the rabbis saw Rosh Hashanah not only as a time of judgment for the Jewish people, but also as the anniversary of the birthday of the world and a time that all pass before God in judgment: in the words of the Mishna and the U’Netaneh Tokef prayer we recited earlier, “v’chol ba’ei olam ya’avrun l’fanekha kivnei maron”, ALL that lives on earth will pass before You like a flock of sheep. Judgment and accountability isn’t just something reserved for Jews, it’s something all human beings have to deal with. And on Rosh Hashanah, as Rabbi Lawrence Hoffman points out in his book “All the World”, we as Jews “appear before God in our capacity as universal man or woman, not simply as a member of the Jewish People. To be sure, says Hoffman, it is Jewish tradition that summons us here to synagogue today, but once here, “we appear naked before God as the human descendants of Adam and Eve in Eden. We are either worthy of continued existence in God’s world or we are not; and if we are not, we engage in teshuvah” (23). We come to terms with who we have been in this past year and attempt to recreate ourselves, and the world, in a better image going forward. Hoffman adds, “Passover is one bookend in Jewish time, the particularistic one, the High Holy Days are the other bookend, the universalistic one, recalling that as much as we are Jews, we are also members of the world community, with a mission to advance the well-being of the world in which we find our existence” (23). This is right in line with the Aleinu insight of appreciating our particular peoplehood while situating it firmly in the context of the universal human experience and consequently embracing our mission of contributing to the betterment of the world. Clearly this universal stamp is all over our machzor, and all over these High Holy Days, even when we are in the midst of our peak season of focusing on our own distinctly Jewish practices and rituals. But this theme isn’t just found during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, it’s found in our Shabbat liturgy every week of the year, in the Kiddush. The first paragraph of the Kiddush focuses on Shabbat rooted in the creation story—God created the entire world and all life within it, and then carved out a 7th day in the cycle to rest once the creative process was completed. The second paragraph of the Kiddush adds another component: it refers to Shabbat as both a memorial for the act of creation, and a remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt, noting “ki vanu vacharta, v’otanu kidashta mikol ha-amim”, “God chose us and sanctified us from all the nations” by giving us the Shabbat. In the Kiddush we move from Shabbat as a universal gift in response to a universal act, to Shabbat as a gift to the Jewish people as part of a particular act of redeeming Israel from Egypt. Clearly we would not have been redeemed from Egypt had we, and the rest of humanity, not been created in the first place. Every week, we are charged with holding on to both contexts of Shabbat when we recite the Kiddush. So how do we navigate this particular vs. universal tension in practice? Well, as with so much else in Judaism, it’s a balancing act. On the one hand, we focus inwardly on the powerful mandate of building our own community, learning as children and as adults about our Jewish tradition, and turning that learning into active Jewish living, observing Shabbat and holidays, eating a traditional Jewish diet through the laws of kashrut, and engaging regularly in personal and communal prayer. And on the other hand, we focus our gaze outwards, looking to reinforce the bond we share with the rest of humanity and do our part to elevate those who need lifting up. There’s a famous maxim from Pirkei Avot, one of our earliest rabbinic collections of wisdom literature from 2000 years ago. It is “Im Ein Ani Li Mi Li—U’ch-she’ani l’atzmi, mah ani”? If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And if I’m only for myself, what am I? It’s a compelling call for both particularism and universalism in our approach to living. But there’s also a third part of the maxim: “V’im lo achshav—eimatai”. This task of looking out for both our own interests, and those of others in the world around us, is imbued with urgency. We can’t put it off, says Pirkei Avot, because we’ll just keep coming up with excuses. So today I’ll offer you a pathway to fulfilling the mandate of helping others besides ourselves, by calling to your attention the impactful work of our Shearith Israel Social Action Committee, headed up by Mindy Fagin and Andrea Solka. Here are just a few of the things they’re currently working on:

This week I ordered the newest tallit in Gabrieli’s line, one of only 72 individually numbered special blue and white tallitot made in celebration of Israel’s 72nd birthday back in May. No, I didn’t need a 17th tallit—I just loved the design and wanted to support my friend Ori Gabrieli’s business as it suffers with no tourism during the pandemic. But it’s fitting in light of my comments today that the atara, the collar, of this tallit is embroidered with the words “V’ahavta L’rey-acha Kamocha”, love your neighbor as yourself, from the book of Vayikra, Leviticus. We do have to love and value ourselves and treasure what makes us unique, but even as we work hard to develop our particular Jewish identity, we have to value our neighbors and reach out and work hard to help them too. And in this small and very connected world we now find ourselves living in, when people all over the globe are struggling with the impact of the same pandemic, where geographic or perceived distance can be bridged in one Facetime call or online gathering, we have lots more “neighbors”. Two brothers, Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman wrote a catchy little melody back in 1963, the lyrics might be vaguely familiar to you: “It’s a world of laughter, a world of tears, It’s a world of hopes and a world of fears; There’s so much that we share, that it’s time we’re aware—It’s a small world after all”. Zeh Olam Katan M’od. It’s a small world after all, so our reach can extend further than ever before, in our own backyards and beyond. But that just means there’s that much more we can do to pitch in. What do you say we get started? Im lo achsav, eimatai. If not now, when? Shana Tova, and Shabbat Shalom. Watch this sermon at vimeo.com/460269520  Parashat Vayishlach 5780 12/14/19 Rabbi Ari Sunshine Earlier this week I was in Boston, along with our president, Shirley Davidoff, and our Chief Operating Officer, Kim West, for the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and the Rabbinical Assembly’s joint “20/20 Judaism” conference, a conference for the lay and rabbinic arms of the Conservative Movement. As an aside, when I found out that the Reform Movement’s conference this week was being held in Chicago, I couldn’t help but wonder: note to conference organizers, would it be too much trouble for you to plan winter conferences in WARMER PLACES? I’m just sayin’… In any case, heavy jackets aside, the convention was bustling and lively, with about 1400 people in attendance, including some staff, volunteers, and exhibitors. I’m not sure if it’s the largest convention USCJ and the RA have ever had, but it certainly was the largest in some time, and there was a great deal of energy in the building from convention-goers. As you might expect, we had a series of large group, full-convention plenaries, including the opening session on the topic of “Why Are We Dreaming Together?” featuring a keynote address by NY Times columnist Bari Weiss; a session on “Why Be a Conservative Movement” featuring a dialogue with the leaders of the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Rabbinical Assembly, USCJ, and the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies; and a session on “Will We Serve the Jews of Today and Tomorrow?”, looking at research regarding Jewish youth today and where they’re at. In addition to thought-provoking presentations to the entire convention body that fed our minds, we also gathered together to listen to, and sing along with, the engaging and inviting styles of contemporary liturgical singers like Joey Weisenberg from Machon Hadar and Rabbi Josh Warshawsky, feeding our Jewish souls with the uplifting ruach, spirit, of these moving encounters. We also had ample opportunities over meals and coffees to network, idea share, and brainstorm, with colleagues and friends from all over the Conservative Movement—keep in mind the Movement spans not just the U.S., but also Canada, Latin America, Israel, and Western and Central Europe, not to mention in places as far away as Melbourne, Australia! And of course, there were a number of slots in the convention schedule for breakout sessions where we could select topics that were of most interest and relevance to individual convention-goers. In one such session I attended, entitled “Who are Today’s Conservative Jews?”, we were presented with combined data from surveys conducted of the Jewish communities in Boston, Pittsburgh, and Washington, DC, in 2015, 2017, and 2017, respectively. That data was also compared at various points in the session to findings from the 2013 Pew Research Center study of the American Jewish community and framed to offer us some potential takeaways from the available data. Here are a few interesting stats: when asked in these surveys what denomination Jews identified with, the Pew Study had 35% identify Reform, 18% Conservative, 10% Orthodox, 6% Other, and 30% No Denomination; and the merged data of the other three studies came up with 32% Reform, 19% Conservative, 6% Orthodox, 2% Other, and 41% None (which included Secular/Cultural and “Just Jewish”). Another stat: for those who, when asked, identify denominationally as Conservative Jews, 57% of them are members of synagogues, with 32% belonging to Conservative synagogues specifically and 25% belonging to other types of synagogues; whereas 85% of those who identified Orthodox are members of any synagogue, and 41% of those who identified Reform are members of any synagogue. When it comes to age groups, one might be surprised to find out that the percentage of those who identify denominationally as Conservative barely varies whether the person asked is 18 or over 80 or anywhere in between—the percentages hold steady in a very narrow band at 18-21% throughout that timeline. Unsurprisingly, where the numbers vary more are in the synagogue affiliation rate itself, with only 25% affiliation between ages 18-34, moving up to 36% affiliation from ages 35-49, peaking at 41% between ages 50-64 and then trending slightly downward to 37% from ages 65-79 as well as age 80+. A few other stats about behaviors and attitudes in these 3 Jewish communities that were surveyed: of those who identify Conservative--

Among the takeaways presented from this data, our session leader, a researcher at the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University, noted that the data complicates our understanding of the label “Conservative” in that there are Conservative Jews who are not synagogue members and there are also members of Conservative synagogues who don’t actually identify as Conservative Jews denominationally. It certainly raises important questions about who we’re currently serving, and who we might yet serve. The fact that Millennials and the Gen Z generation are still affiliating at lower rates than Gen X and Baby Boomers is one that has been consistently noted in recent survey data and challenges us as modern Jewish institutions to continue to create more entry points and lower bars to participation into synagogue life and Jewish life in general. I was pleased to learn that, in the communities studied, 57% of Jews who identify as Conservative Jews are members of at least one synagogue, whether the synagogue itself is Conservative or an independent minyan or affiliated with another movement—that number seemed higher than I would have expected. And I was likewise encouraged to see some of the behavioral and attitudinal data that I shared with you a couple of minutes ago, which suggests, as the Pew Study data suggested as well, that Jews who are identifying as Conservative on balance are relatively engaged Jewishly, both in ritual practices as well as in supporting Jewish community here and in Israel. So where does all of this leave us? At the outset of today’s parasha, when Jacob is anticipating his reunion with Esau, knowing Esau is coming his way with a large company of men and not knowing Esau’s intentions for him, the text says “va-yira Ya’akov m’od”, Jacob was greatly frightened. Midrash Bereishit Rabbah, a collection of rabbinic legends on the Torah from close to 2000 years ago, teaches us (76:1) that “two people received God’s assurances, yet they were afraid; the chosen one of the Patriarchs—Jacob—and the chosen one of the Prophets—Moses—despite the teaching from Proverbs (3.5) to “trust in God with all your heart”. Thus, according to the Midrash, the Jewish people in other precarious moments in our history—like in the days of Haman and the Purim story, for example--could justify their own fear by saying, “If our ancestor Jacob, who had received God’s assurance of protection, was nevertheless afraid for his survival, how much the more so are we justified in feeling afraid?” Jacob’s example illustrates that fear, or anxiety, is actually fully compatible with deep faith. A number of scholars and sociologists have, in the last 10-20 years, sounded the alarm bell for Conservative Judaism, warning that the Conservative Movement is rapidly heading for extinction. So, should we be afraid of what they’re saying? Should we be feeling hopeless for the future, or perhaps even fearing for our survival as a Movement? Friends, I think we should take a page out of our ancestor Jacob’s book. Namely, on the one hand we should embrace the healthy anxiety that some of the statistics may cause us, because it is out of this anxiety and concern and even fear that a meaningful way of Jewish life is being lost, that we are forced to rise to the challenge. We must continue to do more outreach, embrace innovation, and passionately and energetically model Jewish engagement and practice that is both traditional and adaptive, and thought-provoking for our minds and inspiring for our hearts and souls. And on the other hand, we should not just embrace our anxieties on this issue, but we should also have faith: